Eye magazine is the quarterly review of graphic design for artists and designs professionals. In issue 88, I wrote about the creative history of computers. Here’s the article in full:

Digital history begins with the birth of the computer. From Charles Babbage’s Difference Engine to the code-breaking machines of Bletchley Park, early computers were used to solve mathematical problems. In the wake of the Second World War, research units such as Bell Labs began exploring the creative potential of these machines. By the 1970’s computers had become part of everyday life – digital culture had arrived. However the first flickers appeared during the previous decade or so as a direct result of the Space Race.

On the 4th October 1957, the Soviet Union surprised the word by launching the first man-made satellite into space, Sputnik 1. Pride hurt, the US formed the Advanced Research Projects Agency (ARPA). Over the next decade, billions of dollars were poured into scientific research, eventually putting a man on the moon in the ultimate display of one-upmanship. However, space travel wasn’t the only beneficiary of this funding bonanza, a huge investment was also made in the emerging field of computer science.

ARPANET, the first incarnation of the Internet, is the most famous outcome of this investment but ARPA’s legacy extends much further, pervading almost every aspect of digital culture. One of the main recipients of ARPA funding was the Massachusetts Institute of Technology (MIT). In Autumn 1961, a PDP-1 mainframe computer was installed in the Electrical Engineering Department. The first thing the students did was create a game. They called it Spacewar! – the first computer game.

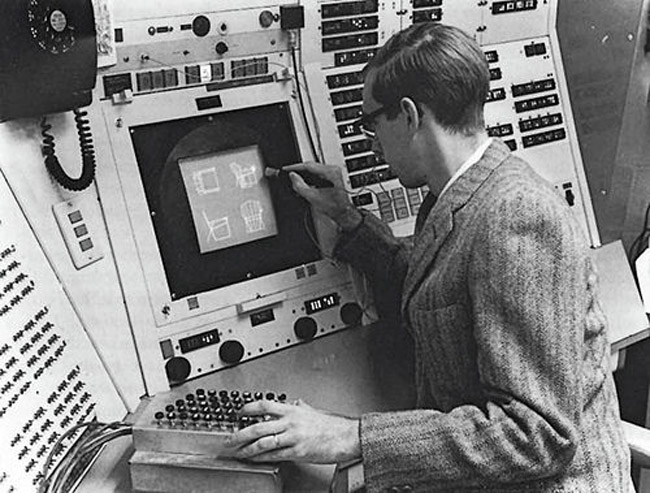

The next breakthrough at MIT was the Graphical User Interface (GUI). In 1963, Ph.D student Ivan Sutherland developed SketchPad, the first computer aided design tool. Incorporating the world’s first graphical interface and a host of other groundbreaking features, it was a stunning achievement. When asked, “How could you possibly have done the first interactive graphics program, the first non-procedural programming language and the first object orientated software system, all in on year?” He replied, “Well, I didn’t know it was hard.”

Following his Ph.D, Sutherland joined ARPA to run the newly established Information Processing Techniques Office. He was given $15 million and told to “go sponsor computer research.” A number of Computer Science Departments emerged as a result. Charles Csuri started a Computer Graphics programme at Ohio State University, where he produced Hummingbird, an early computer animation consisting of 14,000 frames printed to microfilm and photographed. David Evans founded the Computer Science Department at the University of Utah, without which we would not have the seminal Utah Teapot, a seminal piece of 3D modelling. Another beneficiary was the Augmentation Research Center (ARC) at the Stanford Research Institute. Led by Douglas Engelbart, the ARC team built on Sutherland’s work, adding hypertext and the mouse. The iN-Line System (NLS) was publically revealed at the 1968 Joint Computer Conference at what became known as The Mother of All Demos, a demonstration that would change the face of computing forever. For an industry used to dealing with punch cards and command lines, a mouse driven virtual desktop incorporating windows, menus, icons, links and folders was a gigantic leap.

Westerns, Pong and nudes

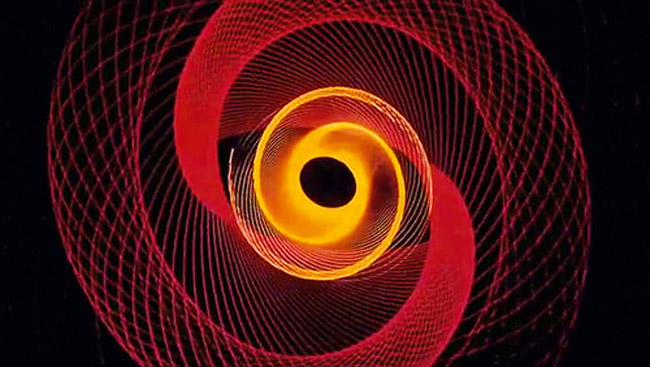

In parallel to the computer scientists, a wave of artists were starting to experiment with computer generated graphics. Chief among them was John Whitney Snr. From his experience working with anti-aircraft guns, Whitney realised their control mechanism could be used like a giant spirograph. The resulting slit-scan animations were spectacular, most famously appearing in his 1958 collaboration with Saul Bass on the title sequence of Vertigo. Whitney went on to pioneer computer-generated animation using a similar algorithm-driven technique.

A frame from Saul Bass’s opening titles for Hitchcock’s Vertigo, 1958. John Whitney Sr’s slit-scan animations were created by a home-made analogue computer, anticipating digital algorithms.

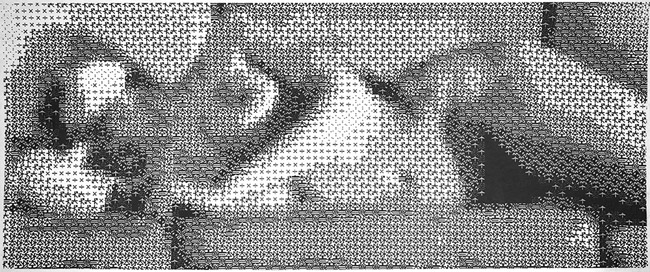

Bell Labs also benefited from a generous grant from ARPA. Between 1961 and 1967, programmers and artists including Leon Harman, Ken Knowlton, A. Michael Noll and Lilian Shwartz worked together to create some of the first computer generated artworks. Highlights include Ken Knowlton and Leon Harman’s Studies in Perception 1, the first computer generated nude (1966), Lillian Schwartz’s Pixillation animation (1970) and Michael Noll’s Computer Composition with Lines (1964). Their work, and the work of their contemporaries, was celebrated in 1968 by Cybernetic Serendipity at the Institute of Contemporary Art. An exhibition that demonstrated beyond doubt the creative potential of computers.

Leon Harmon and Kenneth Knowlton’s reclining nude, 1966. An image of the dancer Deborah Hay was dissected into a grid and each square assigned an icon according to its halftone density.

This potential had also been recognised by Ralph Baer, who came up with the idea of playing games on a TV set. By 1968, he had built a prototype he called Brown Box. He licensed this ball and paddle system to Magnavox and it made its commercial debut as the Odyssey in March 1972, launching with a simple table tennis game. Nintendo secured the right to distribute the Odyssey in Japan and Atari were quick to build a coin-operated version, which they called Pong. Two giants in digital culture had taken their first steps. Baer had taken video games out of the computer lab and into our homes, inventing a new entertainment medium in the process.

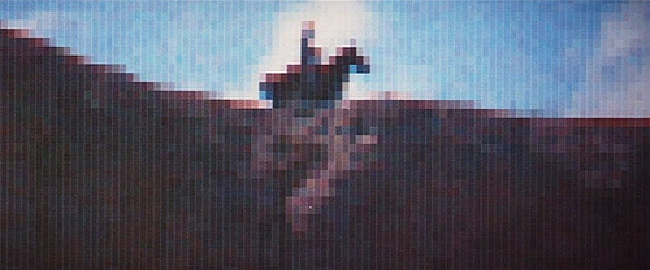

The work of pioneering computer artists and video game designers caught the attention of author turned film director, Michael Crichton. In 1973, he approached John Whitney Snr for help with his first Hollywood film, Westworld. Whitney turned the job down but his son, John Whitney Jnr, took on the challenge. Working with the technology company Information International Inc – Triple-I – he proceeded to create Yul Brynner’s pixellated robot vision, the first computer-generated image (CGI) to appear in a film.

The first use of CGI in a Hollywood movie: frame from Westworld, 1973, written and directed by Michael Crichton. The robot sharpshooter played by Yul Brynner sees his quarry as a pixellated outline. Effects by John Whitney Jr

The new Sketchpad is a Mac

John Whitney Snr also had an indirect hand in the next CGI milestone. Larry Cuba, his collaborator on the seven-minute long 1975 masterpiece Arabesque, went on to create the Death Star briefing sequence in Star Wars, the first extended use of CGI in a film. George Lucas immediately saw the potential, settin up a Computer Division within Lucasfilm to create the special effects for The Empire Strikes Back. Within this division sat The Graphics Group, which eventually evolved into Pixar, taking CGI to infinity and beyond.

Meanwhile, several of Engelbart’s team had gone on to develop the groundbreaking Xerox Alto. But it would not be Xerox that steered the course of modern computing. On a visit to Xerox PARC, Steve Jobs saw the GUI at first hand. In 1983, Apple released the Lisa, the first home computer with a GUI and mouse. The next year came the Macintosh. The image used to promote the machine was a computerised version of Hashiguchi Goyo’s woodblock print, Combing Hair. The image had been made in MacPaint, Bill Atkinson’s pioneering graphics package that owed much to Sketchpad. The image said everything that needed to be known about Apple’s new computer. It was more than a calculating machine – it was a creative tool.

Thirty years on, with the birth of multi-player gaming, the Web and the Smartphone, the digital world has been seamlessly integrated into every aspect of our lives. Engineers may have invented the medium but artists and designers shaped it. Thanks to them, digital culture has simply become culture.

Thanks to Eye for allowing me to reproduce this article.

Pingback: Joana Moll – Deep Carbon – RESEARCH VALUES 2018