In the early ‘70’s, following the launch of ARPANET, several packet-switching networks emerged. Robert Kahn had the idea of joining them up. To do this, they would need a common set of rules.

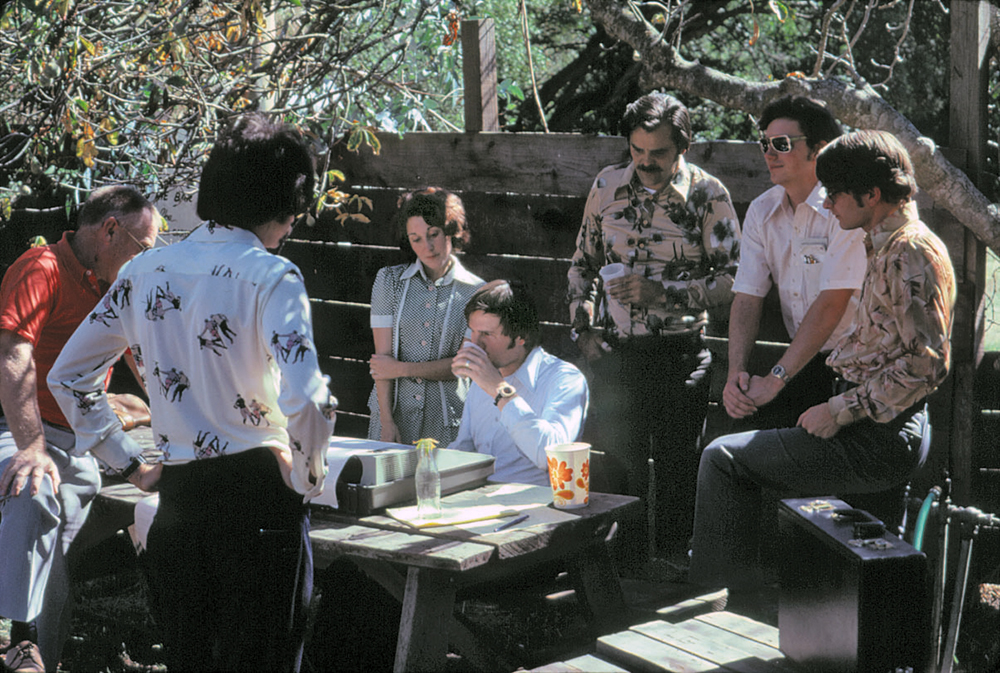

One of these networks was a packet radio system operated out of a converted bread van provide by Stanford Research Institute (SRI). One of its regular stops was the Alpine Inn. Known locally as Zott’s, it was described in 1909 by the president of Stanford University as “unusually vile, even for a roadhouse, a great injury to the University and a disgrace to San Mateo County.” This view was not shared by Stanford students.

It was outside Zott’s, on 22nd November 1977, that the van sent a message to London via Norway and back to California by satellite. It travelled 90,000 miles in two seconds. At that moment, outside a biker bar in Silicon Valley, the Internet was born.

This first successful test used TCP but as the Net grew, more protocols were required. User Datagram Protocol (UDP) was created for files where speed was more important than sequence, such as voice and game play. Internet Protocol (IP) was developed at a higher level to label and transport packets. This suite of protocols became known as TCP/IP. Its evolution over the next twenty years was managed by one of the driving forces of the Internet, Jon Postel.

In 1982 the decision was made to convert all networks on ARPANET to TCP/IP by the end of the year. On 1st January 1983 the switch was made permanent and barely celebrated. It is only with hindsight that we realize what a momentous occasion this was. It heralded the start of the Information Age.

Kahn and Cerf get the glory but like most things, the success of TCP/IP is down to many people. Chief among them perhaps is Jon Postel. The behaviour he encouraged, known as Postel’s Law, seems wise beyond the implementation of TCP/IP, “be conservative in what you do, be liberal in what you accept from others.”

This is an extract from 100 Ideas that Changed the Web, available on Amazon UK and Amazon US.