Co-curated by Irini Papadimitrou and Bronac Ferran, Brown & Son’s Art that Makes Itself exhibition at the Waterman’s Art Centre is a retrospective of almost fifty years of Paul and Daniel Brown’s considerable contribution to the field of computer art.

I was honoured to be asked to contribute an essay to the exhibition catalogue. Here it is, reproduced with the kind permission of the curators and artists.

We need more exhibitions like Brown & Son, Art That Makes Itself. Not only does it celebrate the inter-generational history of computer art, it’s a catalyst for digital preservation.

I’ve been involved with the preservation of websites since 2010. One of the first projects I archived and exhibited was Danny Brown’s Noodlebox from 1996. Danny supplied the HTML framework and compiled Director files (two HTML files, four GIFs and 36 DCR files). I bought a machine from the era, downgraded the OS to System 7, installed Netscape Navigator 3 and a Shockwave plugin and we were good to go. Whilst it was tricky to source and install the software, especially the plugin, recreating the exact environment from fourteen years earlier was a realistic ambition.

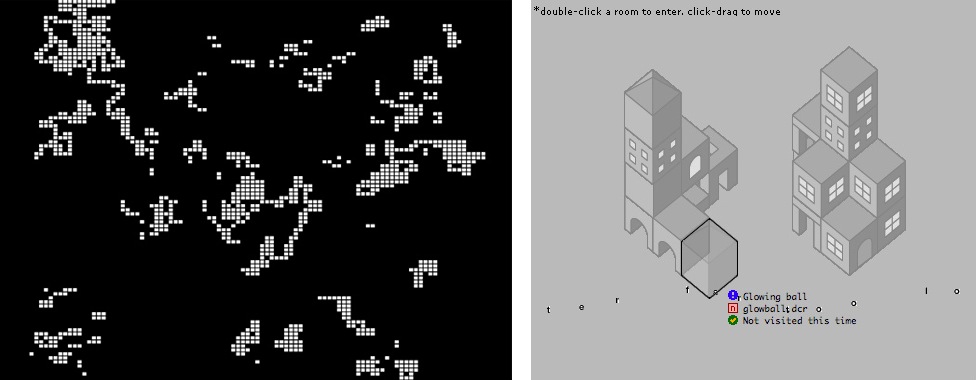

More recently, my digital archaeology investigations have expanded into computer art, video games, and CGI. I was asked to tell the creative history of computers in 100 projects as part the Barbican’s Digital Revolution exhibition last summer. As an iconic example of generative art, I was keen that Builder/Eater was one of the artworks in the show. Paul wrote Builder/Eater in DG assembler language on a Data General Nova 2 minicomputer in 1977, the year Star Wars was released. Like Star Wars, two opposing forces battle it out on screen. One random walk switches pixels on, the other switches them off, creating a non-repetitive animation that will never be resolved.

When I approached Paul about how we might exhibit Builder/Eater, it was obvious using the original hardware, software and media was not an option. Not least because he no longer had the code! Even if a copy of the code had survived and we could source a Data General Nova 2 minicomputer, the six-foot rack would not be practical for a touring show. Even at the time, Builder/Eater was only ever exhibited at The Slade School of Fine Art where Paul and the DG minicomputer were based.

The version Paul recreated, shown in Art That Makes Itself, was programmed in Processing and runs on a Raspberry Pi outputting to a 1980s Sony CRT monitor. Despite the software and hardware updates, the only concession to the underlying code was to tweak the run speed. In the original version, the screen was refreshed as fast as the computer would run. Today, the refresh rate had to be throttled to reflect the processing power of the 16-bit DG Nova 2. Although only the random walk algorithms themselves are true to the 1977 version, witnesses testify that the resulting artwork is virtually identical to the original.

Builder/Eater is a fitting metaphor for digital preservation. The battle between conservators and media obsolescence is ongoing, never to be fully resolved. It’s unrealistic to preserve the original hardware and software indefinitely. The aim has to be to sympathetically migrate the work to new platforms and technologies whilst respecting the artist’s intent. My personal preference is to house a new hardware within the original cases, maintaining the user experience but this is one of many solutions.

Respecting the artist’s intent is straightforward if they can be asked but what if they can’t? Nam June Paik playfully changed his works with each installation. Who’s to guess how he would present any of his work now? And the views of the artist can change. In the 1970’s Paul, like many of his contemporaries, was hugely influenced by the auto-destructive art of Gustav Metzger and embraced the ephemerality of his work. As he has got older, his views have changed.

A constant cycle of migration can check media obsolescence but there’s more to conserving digital artwork than updating the hardware and software. Computer artists are essentially hackers, breaking the rules and pushing back boundaries is part of their DNA. Collaboration, subversion and making technology do things they were not designed to do are common attributes of their work. All complicate the preservation process.

An issue for web-based work like Danny’s is that any single artwork may exist in a multitude of forms. Noodlebox, for example, runs on multiple platforms – Mac and PC and a plethora of browsers. Noodlebox also rejects the traditional menu system, instead creating an interactive landscape of building blocks. Behind each building block is an interactive experiment but more importantly, each building block is moveable, the user can effectively design their own navigation system. Which combination represents an authentic experience?

Collaborative pieces also present a unique set of problems. Sometimes it’s necessary to preserve multiple versions. For example, The World’s First Collaborative Sentence, put online by Douglas Davis in 1994 stopped working in 2005. When it was ‘fixed’ in 2012, two versions were made. One recreates the sentence right up to the point where it stopped working, the second is a re-coded, live version of the sentence, which visitors can add to, just as they did with the original work.

Subverting third-party services complicates things again. Cory Arcangel’s Punk Rock 101 consists of a transcription of Kurt Cobain’s suicide note with embedded Google Ads. When it came to Google’s attention, they pulled the ads. The work only exists today as a screenshot. Works like Chris Milk’s The Wilderness Downtown and James Bridle’s Dronestagram are equally vulnerable.

How artists address issues of continuity differ from case to case. Some, like Alexei Shulgin, embrace the temporary nature of technology. Form Art, subverts HTML, creating form out of function. It evolves as browsers evolve, demonstrating the unknown future of the Web. Others, like Olia Lialina, capture a moment in time. Although Lialina tolerates her work My Boyfriend Came Back From The War being exhibited on contemporary hardware, she insists it is shown on a period browser and downloads at a speed equivalent to that of a 33k modem. Lynn Hershman is happy for LORNA to be shown on interactive DVD rather than laser disc but draws the line at a PC version. JODI request their site, wwwwwwwww.jodi.org is simply shown as a slideshow of screenshots. Cory Arcangel’s Photoshop Gradient Demonstrations exist simply as sets of instructions.

Ruse Laboratories offer an alternative approach, paring the work down to the underlying algorithm. Their recent Algorithm Auction examined algorithms for their aesthetic merits as well as their functionality. They curated and sold seven of the most elegant algorithms ever created. Lots included Brian Kernigan’s Hello Word (1978) and the OkCupid Compatibility Calculation (2003).

This raises the question what is the digital work? Is it the source code or the compiled file? Is it a set of instructions? Is it the data, the logic or the presentation? Is it the first version, bugs and all, or is it a bug-fixed future release? Does it include auxiliary software like the operating system, firmware or software package it was created on? What about the hardware? What about the input and output devices and other peripherals? Or is it purely the underlying mathematics?

By exhibiting their work, artists and curators are forced to answer these questions. When the work is acquired or borrowed by a major gallery, the curator is likely to use a recognised metadata framework such as PREMIS (PREservation Metadata Implementation Strategies). Smaller exhibitions take a more hands on approach but are equally informative, the process existing as a use case for future migration exercises. Even if the object can’t be preserved and is shown as screenshots or in print, the catalogue and surrounding conversations helps to preserve its cultural significance.

Migration is not just an issue for the art world. Artists and conservators also make a valuable contribution to wider digital preservation challenges. Industry, cultural institutions, government agencies and individuals across all aspects of life face the same problems. Multidisciplinary individuals, like digital artists, who have both the creative insight to retain the spirit of the work and the practical skills to manage technological change, are well placed to lead the conversation.

Software shapes our lives. When historians look back at the digital revolution, they’ll use software to do it. If they can do so successfully, it will be at least partially thanks to artist-engineer-Jedis like Brown & Son.

2 Responses to The Dark Side of the Digital Revolution