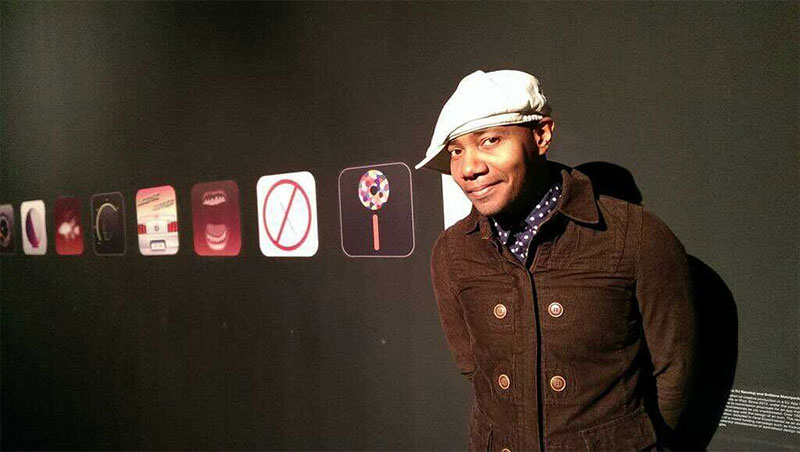

DJ Spooky, That Subliminal Kid, defies pigeonholing. Not only is he a musician and author, he’s a technologist, conceptual artist, academic, philosopher, magazine editor, and with 14 million downloads a pretty mean app developer.

I first heard of DJ Spooky 18 years ago when I was studying under Dr Richard Barbrook and the Antirom art collective at the Hypermedia Research Centre. Someone told me I should check out his collaboration with Ryuichi Sakamoto of Yellow Magic Orchestra fame. Then, I confess, he dropped off my RADAR until I was researching the origins of digital music for Digital Revolution last year. I bought Sound Unbound and Rhythm Science by Paul D Miller and realised that DJ Spooky and Paul D Miller are one and the same. Which explains why he’s four times as productive as most people. He’s the human incarnation of Metcalfe’s Law (the value of a network equals the square of the number of connected users).

Paul’s work has appeared everywhere, his list of collaborators is stunning, he’s been to the South Pole and he’s written a symphony based on the stories of eight atomic bomb survivors, which he’s performing in Hiroshima and Nagasaki later this year. He’s also got a book out, The Imaginary App, a collection of essays about the world changing phenomena that is the mobile App, edited by himself and Svitlana Matviyenko. I was very flattered to be asked to host its UK launch last month at ThoughtWorks, London. Like The New Media Reader did for the Web before it, the 19 essays in the book give us the tools and vocabulary to explore what total immersion in digital culture might mean.

The book is split into four sections. The first section looks at Architecture and how power and control are consolidated by software. The first essay, by Benjamin Bratton, On Apps and Elementary Forms of Interfacial Life examines apps as an interface. The app that sits on our phone is an interface to the real application, most processing occurs on remote servers, AKA the cloud. It’s an interface between other users and it’s also an interface to our environment. Bratton points out that it’s also an interface between the application and our environment. He says, “The mammal user is a provisionally necessary for dragging gigaflop tracking devices through the avenues of cities.”

The book is split into four sections. The first section looks at Architecture and how power and control are consolidated by software. The first essay, by Benjamin Bratton, On Apps and Elementary Forms of Interfacial Life examines apps as an interface. The app that sits on our phone is an interface to the real application, most processing occurs on remote servers, AKA the cloud. It’s an interface between other users and it’s also an interface to our environment. Bratton points out that it’s also an interface between the application and our environment. He says, “The mammal user is a provisionally necessary for dragging gigaflop tracking devices through the avenues of cities.”

Question to Paul: How long do you think we’re provisionally necessary for?

I’m an artist and that puts things in perspective. I’m always cautious about how science can be perceived. It’s so much deeper than the basic premise that we “understand” the world around us: we don’t. Digital media is just a tool and the way Apps have evolved out of the ecosystems of software and hardware as a foundation of modern society would have been unimaginable for a different era. The 19th century thought the future would be steam, the telegraph, and lots and lots of mechanical parts. For the 21st century, bio-tech’s intersection with quantum physics is the event horizon for most of what can be at the edge of knowledge. I sometimes am not sure our species will survive this century. So we are “provisionally necessary” to set up artificial intelligence and see how that will unfold. We probably won’t be able to understand it…

The second section looks at prosthetics. One of the essays in this section by Nick Srnicek is called Auxiliary organs; An ethics of the extended mind. In it, he suggests what makes humans unique is not our intrinsic intelligence but our ability to use tools. There are 3 billion people online, two-thirds of them access the net through a tool they hold in their hand, the smartphone. Unlike other tools – the pencil, the hammer or the gun – the phone does not have a single function, it’s multipurpose. It has more in common with the hand than a utensil – it’s the auxiliary organ of the title.

Question to Paul: Does this make us superhuman or less human?

Probably it’s like we are children playing with toys that we don’t understand. But that is OK. Kids have a lot more fun…

The third section is about Economics. App Worker by Nick Dyer-Witheford discusses the nature of work in the app economy – remuneration, conditions and prospects. In 2008, Apple launched the App Store and officially introduced third-party apps, which according to a NY Times journalist was like “letting a toddler play with his Stradivarius” but actually it was nothing of the sort – Apple totally control the market, writing the rules, taking a cut of sales, getting advertising revenues, get tons of great apps that lock people to the iPhone and a whole load of free R&D, with the developer community taking all the risk.

Question to Paul: Why don’t app developers identify as workers and collaborate rather than compete?

The market for Apps is volatile and there is extremely high compensation if you play your cards right. Of course they’re not going to identify as humble factory workers! They’re going to look at Sean Parker, Mark Zuckerberg, Jeff Bezos etc And that too, is kind of OK. But we need new models for thinking about this kind of aspirational aesthetics. The Imaginary App was thought of as an irreverent collage of different approaches to how Apps have changed the way we look at modernity. From mathematicians like Stephan Wolfram on over to map inventors like Noel Gordon (one of the principal inventors of Google Maps) on over to art Apps like what Scott Snibbe designed for Bjork’s Biophilia App, we’re presented with a dynamically engaged portrait of App’s as they appear both in current culture, and what will be going on in the near future. You can think of The Imaginary App as the past, present, and potential of Apps.

I wanted to inject more politics into the idea that data is not neutral, there are many underlying ideologies about the way devices are put into our society. Apps are a tenuous link between platforms and portals, between ideologies and networks. Apps are just like portals – you have to be thoughtful about what path they take you on. The map is not the territory. The territory is not an App. Press play, loop, re-edit. Repeat.

The final section is about Remediations. From Digital to Tentacular, or From iPods to Cephalopods: Apps, traps and entrées without exit by Dan Mellamphy and Nandita Biwas Mellamphy likens the network of smartphones to the tentacles of a massive cybernetic octopus. However simple and benign they might appear, apps are hyper-camouflaged bait in a predatory framework that aims to appropriate our identities. Apps, they suggest is short for appetizers.

Question to Paul: How nutritious do you think you’d be?

I’d probably be like a shot of wheatgrass – one or two ounces of wheatgrass juice gives you about the same amount of chlorophyll as a couple pounds of carrots and broccoli etc Let’s think of my way of doing this is as a fitness App for the mind… It takes exercise and practice.

An exhibition of imaginary apps runs alongside the book and the book finishes with some of the highlights, my favourite being “The Ultimate App”, which upon launching, charges you 99p and then closes again. “No fuss, no muss.”

If you fancy flexing your mental muscle and peering round the corner into the not too distant digital future, I recommend you keep your eye on DJ Spooky and add The Imaginary App to your reading list.